A Roundtable on African Women Imagemakers in HERStory

By Ethel Tawe for Feminist

IN CONVERSATION WITH TINA CAMPT, CATHERINE MCKINLEY, AMY SALL, VELMA ROSAI, AND AWA KONATÉ

Investigating absences in the archives around African women photographers and filmmakers can seem futile. However, women authors, archivists, artists, researchers and culture workers today continue to lead a long tradition of reactivating the ongoing event of image-making, by shaping our reading of these archives while projecting them forward. In a bid to gain some perspective, I speak with some of these women including Black feminist theorist Tina Campt who proposes the radical notion of listening to images, a counterintuitive practice of attuning our sonic and haptic registers to uncover silences in the archives, beyond authorship and what is obvious to the eye. From this expansive notion, I arrive at African American author Catherine McKinley’s parallels between the camera and the sewing machine: technologies that became modes of agency for African women through self-fashioning and shaping trade economies, as explored in The McKinley Collection (an archive of African photographies focusing on women from 1870 to present). Shaking institutional foundations are Senegalese-American cultural entrepreneur Amy Sall, founder of SUNU Journal, and Danish-Ivorian curator Awa Konaté, founder of Culture Art Society (CAS), whose critical and curatorial research on methodizing archives and reconceptualizing the gaze, challenges us to reflect on the power of cinema and photography on our everyday lives. Taking an artistic approach, contemporary Kenyan artist Velma Rosai is interested in the present tense, creating cultural libraries for those to come through multidisciplinary engagement with archives in her own art and photography. In conversation with these women of the African diaspora, we examine the process of decolonizing archives, gaze, care, and reversing the erasure by honoring African women in lens-based practices.

EThel tawe: To begin with, why do you think a knowledge gap about African women imagemakers exists? What are the ramifications today?

AWA KONATÉ: The gap exists because of gendered perspectives which have favoured the naming and memorialisation of men, despite the extensive presence and involvement of women. The ramifications obviously are that they have been written out of history. Where “found,” their authorship and oeuvre aren’t always granted rigorous care. Often, the ways of accessing the knowledge they produced are through curatorial interpretations that are rendered authoritative through institutional frameworks, though sometimes the existence of their records are disregarded.

CATHERINE E. MCKINLEY: It's quite astounding, really, that there is no real documentation of early African female photographers. We know of very few women in footnotes, like a Nigerian studio owner in the early 1900s, but we don’t know if she simply owned and hired out the machinery or had a practice. Then we jump to Felicia Abban from the era of Ghana's Independence in 1957. People are very quick to accept her as a ‘first’ and as a studio artist, although she herself is a bit uncomfortable with the title of ‘artist’ — which may be about gender, and may be about her actual practice working primarily as a state photographer under Ghana’s first president Kwame Nkrumah. So now, in 2021, we are 30 plus years since the introduction of Seydou Keita and Malick Sidibe to the Western mainstream, but questions of gender are barely emerging in the discourse, even with the huge catalogs of female sitters in African archives.

TINA CAMPT: The presence of women in the [colonial] archive is overwhelming, but at the same time it's so often marked as submissive. In [my book] ‘Listening to Images’ one of the things that I wanted to do was to allow their presence to resonate in terms that are not of the people who photographed them. When I see these commanding presences of women, a question I often ask is: what are the circumstances that allowed this particular image, or any kind of archival document, to be having an encounter with me right now? I think my way back to the creation of that object and how it traveled forward in time to be able to get to me. ‘What was she doing and who felt that they had the right to photograph her?’ In that moment, there's an exchange and you have to think about what is happening within that frame.

Today, what does it take to understand yourself as a filmmaker for example? For men it's a lot easier, it's a role they feel entitled to play. In this search for women imagemakers, the earliest women may or may not be behind the camera. They may be producers, writers, or in the support team. The masculinist model of a filmmaker as controlling everything is a particular inhabiting of power that women aren’t always interested in as marking the structure of their creative practice. We have to open up the category of what it means to be a filmmaker, because sometimes you’re not credited for the work that you do.

VELMA ROSAI: Photography institutionally has been and still is under a white male gaze, which works doubly against Black women. We have been overlooked and less applauded. Historically we weren’t afforded access to the medium. Many were self-taught, few in numbers and no publisher had confidence in featuring African women who didn’t have formal education in the craft. It comes down to patriarchy, race and gender disparities.

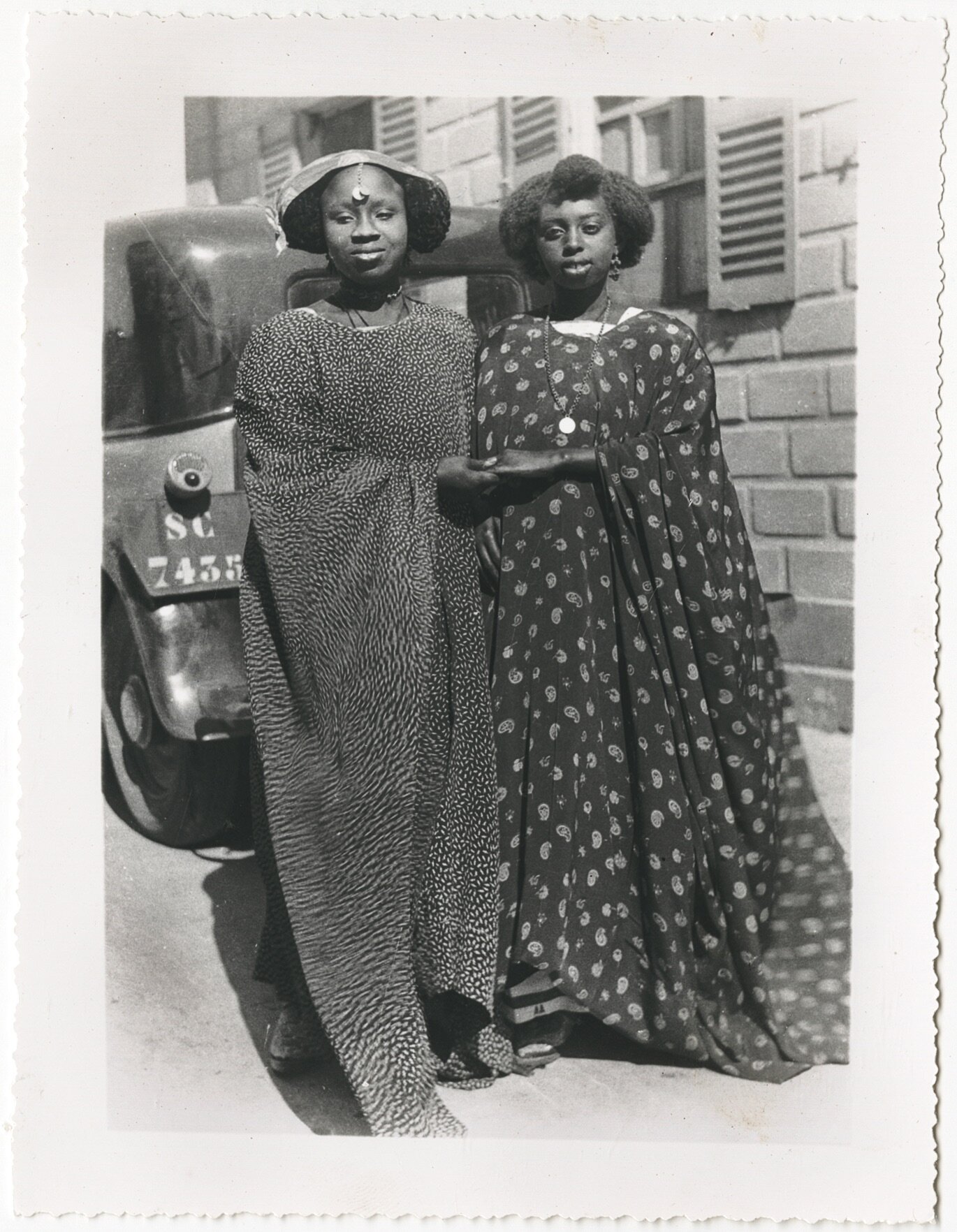

Images courtesy of The McKinley Collection and The African Lookbook.

“I really want to challenge this idea that the gaze is only dominant or top-down.”

E. tawe: In terms of gaze, however you define it, how do you think African women have historically shaped, engaged or subverted power dynamics around the camera, either individually or collectively?

AMY SALL: African women have used the camera to assert their rights, voice and power, and to make evident the issues that have historically affected them. An example I am drawn to is Mossane (1996) by Safi Faye in which light is shed on the issue of arranged marriages, and how the needs and wants of young African women are often ignored because of tradition and certain cultural norms. What I define as The African Gaze in cinema is held, mediated, and informed by the African experience (the specific and universal), and confronts a colonialist narrative. The African Gaze subverts the camera, the same tools colonizers weaponized and used to dehumanize African people, are now used to reclaim truth, agency, autonomy, sovereignty.

A. KONATÉ: African women have always been at the forefront of shaping discourses beyond the camera. This includes the field of cultural work, where their influence has been imperative even if not widely known. Because of difficulties locating specific past names behind the camera, one way to look at this is African women as sitters. In commercial photography, their aesthetic choices, active negotiations with photographers, and camera conventions are important parts of bringing into being the literal contents of an image, thus to a large extent they profoundly shape the dynamics of the gaze and authorship. Today’s landscape follows a long-standing trajectory of women who have always done archival work.

C. E. MCKINLEY: When Western attention was first given to early African photographies, most of the scholarship was concerned with "the gaze" and many readings of photos became overdetermined by eyeballing. I'm interested in a foot, an assertion of feeling marked in clothing, the clasp of a hand, the beads marking protection and beauty left on the shins of a nude woman in a colonial parlour. And when it is about an interaction with the lens, I'm interested in how female sitters just as often eat the lens, as if saying the camera is there for them; they are not its pawn.

T. CAMPT: I really want to challenge this idea that the gaze is only dominant or top-down. It's not really about getting others to see through our eyes, but to understand that their relationship is not one of mastery. There are ways of presenting Black visuality that alienate white people and they have to come to terms with that, which means you are confronting a Black gaze. During the post-independence moment, many of the references were still about a postcolonial relationship but lived and represented differently. I think it's really important to not think about independence as a rupture; it’s something African women have been able to bridge. I often like to emphasize that yes there are historical ruptures, but individuals have had to bridge it because they are existing in continuity through it.

E. TAWE: In your work as an educator/researcher, what ways do you think institutions have failed at reversing the erasure of African women imagemakers in history, and present? In what ways are independent platforms decolonizing and closing this gap?

A. SALL: When it comes to reversing the erasure of African imagemakers, I think institutions suffer from lack in many categories: lack of foresight, lack of will, lack of diversity, to name a few. African scholarship, culture and art are chronically minimized, flattened, gate-kept, and often mediated by non-Africans in these institutional spaces. SUNU Journal is dedicated to the accessibility of Pan-African intellectual, cultural and artistic production, and it is African-operated.

A. KONATÉ: Where minor attempts have been made by institutions to reverse erasures there is a particular favouring of diasporic image-makers and glaring omittance of African women, notably continental, despite their ongoing conversing. Beyond the gendered dynamics of the past and present canonisation, I also think there is a wider misconception that African women image-makers do not produce complex readings of their subjects. Thus one encounters often didactic framings of their works. CAS, and many others, are bridging the gap by creating a space where their artistic and intellectual labour is honoured, respected, and importantly, made widely accessible.

T. CAMPT: I think there are a number of different levels in which we need to engage with decolonizing the archive. One is the obvious level of institutional control: who dictates the rules of access for archival holdings and where are they? How can we decentralise that process? That’s the biggest challenge, the institutional level of control. One of the things that I and some of the people who I admire do is to read against the archive; we read against the official narrative of who is supposed to be speaking and from what position are they speaking.

E. Tawe: How do you think, if at all, your practice departs from male artistic traditions in African history? Is this important to you?

V. ROSAI: It is important to me because my photography has an autobiographical streak. I am a venn diagram of overlapping experiences. Placing myself in front of the camera is an intentional reclamation of self from traumatic histories of how African women were eroticized and exoticized by the colonizer. I get to control how I want to be seen and represented. My practice also mines so much inspiration from African cinemascapes and images which document a postcolonial African identity — especially from my Kenyan mother’s old photo albums: the silhouettes, tones, and composition play a big part in constructing the images I produce today. A cyclical continuum. My mother studied photography in the 70s and her archival imagery means so much to me today.

E. Tawe: What is the relationship between the camera and the sewing machine, and how have African women shaped this throughout history?

C. E. MCKINLEY: The camera and the sewing machine were two colonial instruments that were introduced to Africa in the mid-1800s. At first, both were the reserve of colonialists, and then African royalty, before slowly becoming democratized. African women seized the machinery; the sewing machine in obvious ways. We know that as sitters in African studios in particular, they owned the camera, whether through fashioning themselves in ways that are subversive, or in how these photos display power and self-possession. The camera is there for them, and not the opposite.

E. Tawe: How has your Black Feminism been a tool for reading and investigating visual archives in a way that contributes to reversing the erasure?

T. CAMPT: My Black feminism is more than gender, it's more than the assertion of equity and equality. It is really about ‘who are my teachers?’ and ‘who has taught me to think?’. The feminists who have taught me to think do so as part of a practice of mutual support, respect, lifting each other up in moments when we have been resigned to obscurity or invisibility. Black feminism to me is a part of a practice as opposed to a theory. It is one that encourages me to study collectively and collaboratively, to cite people back and forth. To recognize that any of the work I produce is part of a conversation that would not be possible without other people who I am reading and who are reading me.

Still from MOSSANE (1996) by Safi Faye

E. Tawe: Who are some African women imagemakers, of past or present, whom you would like to honor today?

V. ROSAI: There are many of us now and we are living in a futile time of progression and great transformation. I love the work of Rharha Nembhard and Tony Gum for example. I love how African imagemakers like Zanele Muholi and Lina Iris Viktor use and reclaim the colour black AND their bodies. Their work is an invitation to immerse yourself into their worlds.

C. E. MCKINLEY: I'd like to honor Carrie Lumpkin, a Saro woman and descendant of a Brazilian formerly enslaved returnee to Lagos who opened a studio in 1907. Fatimah Tuggar (Nigeria/USA) who is wildly under-sung. Patricia Coffie (Ghana/USA), who appeared out of nowhere with a brilliant show at Mary Boone Gallery, and then disappeared completely just as quickly. Her photo, Far From Home (2008), is one of my favorites. This panel alone is remarkable! Watch each of us continue our practice, and with greater contact with each other and the few existing others. There will be some remarkable returns in the next few years.

A. KONATÉ: So many, but I’ll share a few. Of the past: Adelia Sampaio, Madeline Anderson, Ateyyat El- Abnoudy, Safi Faye, Sara Gomez, D. Elmina Davis, and Sarah Maldoror. Of the present: Hachimiya Ahamada, Candice Onyeama, Iréne Tassembedo, Euzchan Palcy, Noutama Bodomo, Runyararo Mapfumo, and Touda Bouanani.

A. SALL: The African women who have contributed greatly in this space, past and present, all deserve their flowers and recognition. A few I would love to honor are Safi Faye, Anne Mungai, and Sarah Maldoror. There are African women imagemakers we don’t know or know very little of, like photographer Wesal Mousa Hassan. I hope all of the unknown/unnamed African women imagemakers become known and named in our lifetime.

THIS ARTICLE HAS BEEN EDITED FOR CLARITY AND FLOW.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ethel-Ruth Tawe (she/her) is a Cameroonian multidisciplinary artist, editor, and creative consultant, exploring African identity and diaspora cultures through visual storytelling. Her practice examines Africa’s ancient futures from a magical realist lens. Image-making, storytelling, and time-travelling compose the framework of her inquiry. Ethel holds an MSc in Development Studies from SOAS University of London and a BA (Hons) in International Human Rights with a minor in Art History & Criticism.

Read more by Ethel Tawe and Follow @artofetheltawe